©Robert Buzzanco

Jim Garrison: I never realized Kennedy was so dangerous to the establishment. Is that why?

X: Well that’s the real question, isn’t it? Why? The how and the who is just scenery for the public. Oswald, Ruby, Cuba, the Mafia. Keeps ’em guessing like some kind of parlor game, prevents ’em from asking the most important question, why? Why was Kennedy killed? Who benefited? Who has the power to cover it up? Who?

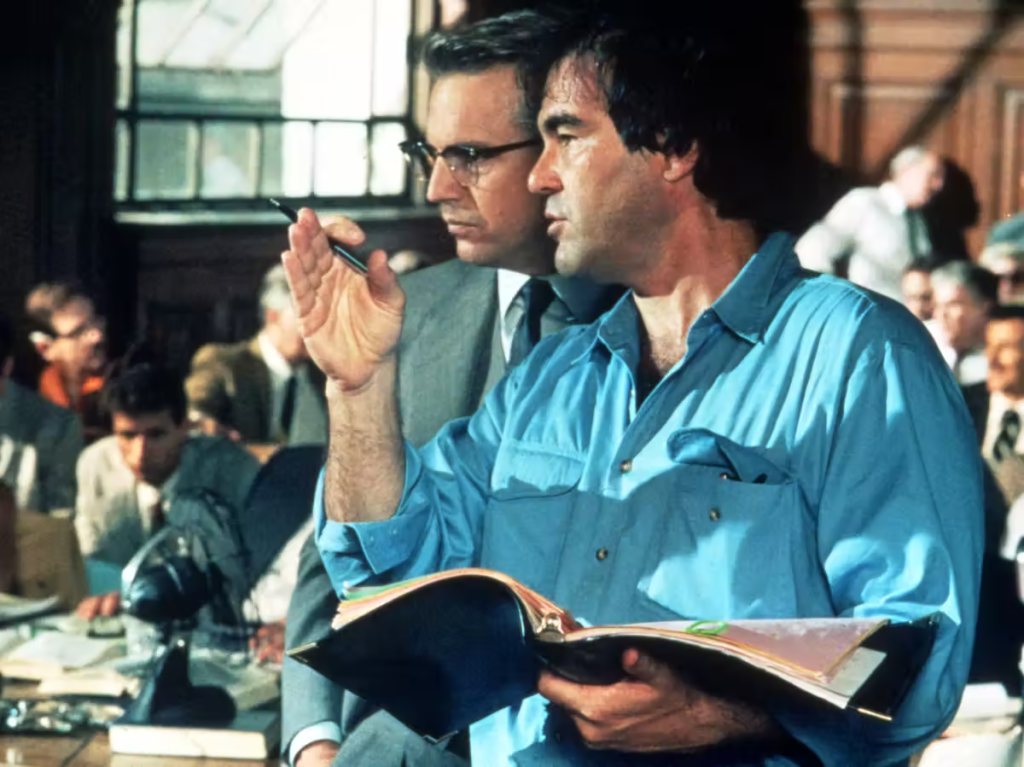

That brief discussion between characters played by Kevin Costner and Donald Sutherland in Oliver Stone’s 1991 film JFK remains at the heart of this entire issue as a documentary about and new cut of the movie are coming out more than three decades later, and it’s a question that Stone has never been able to answer in any meaningful way. The “why” of Kennedy’s assassination, the famous director has contended. was that the young president was breaking away from the entire path of U.S. foreign policy, especially in the post-1945 era.

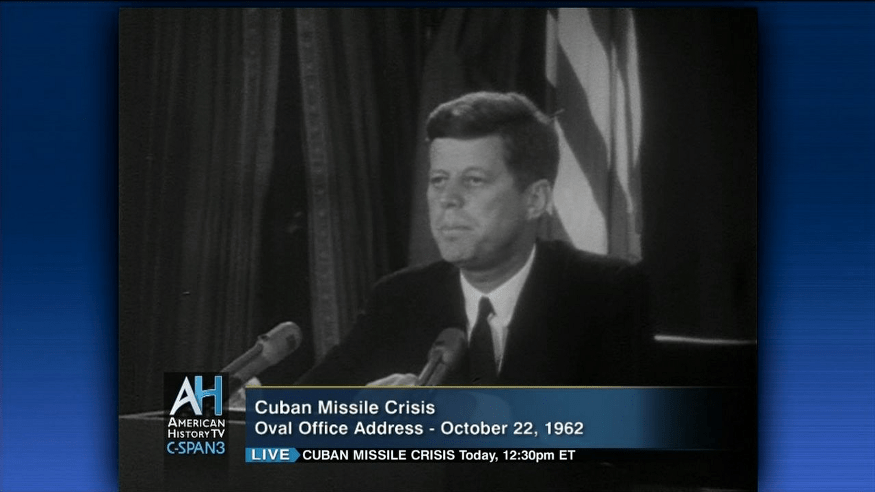

JFK, Stone claimed, essentially had a Road to Damascus and realized that constant wars and interventions, sabotage and meddling in other countries, immense military budgets and a politically-powerful military-industrial complex, far too-independent intelligence agencies like the Central Intelligence Agency and government groups like the National Security Council, and an entire government apparatus profiting from militarism and war had brought the globe to the brink of disaster or even annihilation, especially during the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, and had to end. And so Kennedy was set to withdraw U.S. military forces from Vietnam, ending the growing conflict there, and reach out to the Soviet Union and other Communist countries to thaw and ultimately end the Cold War. And that provided the answer to “why?”

For this turn toward peace, this commitment to beat swords into plowshares, those very forces Kennedy had identified as the beneficiaries of military budgets and espionage and wars conspired to have him killed. While much of the Kennedy conspiracy theory (or theories) focus on the intricacies of Lee Harvey Oswald’s past and his movements, anti-Castro Cubans and mafiosi, magic bullets and grassy knolls, the Texas Book Depository and other physical elements that affected the events in Dallas on 22 November 1963 — an there is abundant documentation on those things — Stone is correct that it’s mostly scenery for the public. The real question, the one that has historical immanence, sui generis, is the “why.” What Stone posits is so massive, so world-historical — a large cabal of state agents working together to conspire to murder the leader of that state for political reasons — that it has to be presented, should have been invented, with a profound and surgical focus on “why.”

Stone’s response, that the military and intelligence communities wanted JFK dead because he was on to them, is more than unfulfilling. It is intellectually specious and an epistemological void to offer up such a theory, and offer no substantial evidence to back it up. The idea that perhaps thousands of state functionaries worked together, secretively, to plot to kill the president, and then maintained that perfidy for decades, is hardly the stuff of rigorous intellectual inquiry. The fact that it has become accepted by a significant number of thinkers, scholars, journalists and others, especially on the Left, is frightening, for it substitutes heroic myths for solid research.

And so this is my response to Stone’s argument that the military-industrial complex, the CIA, even perhaps the Vice President all joined together to kill JFK. It’s a simple argument — that there is nothing in the actual historical record to validate Stone’s claims about Kennedy’s apparent change of heart about peace in Vietnam without victory or ending the Cold War. In fact, the opposite is more true — Kennedy entered political life as an aggressive, militarist liberal who morphed into perhaps the prototypical Cold Warrior of his generation.

In order to show this I’m going to present my argument in three sections. First, I will offer a brief analysis of the reality of Kennedy’s decisions in Vietnam, with a specific emphasis on the U.S role in the coup of November 1963, hardly the action of someone seeking a way out of a conflict, with some discussion of NSAM 263, one of the favorite documents of Stone and his conspiracy followers.

In part two I will discuss a vital yet mostly ignored aspect of this decision — the fact that U.S. military leaders, whom in Stone’s world were so upset by Kennedy’s weakness on Vietnam than they wanted him dead, were in fact themselves never supportive and mostly against any type of military commitment to the state the U.S. had invented in southern Vietnam. I also will discuss JFK’s aggressive foreign policies beyond Vietnam in this section, with a focus on his national security policies in Europe.

Finally, in part three, I will discuss Kennedy’s programs and plans for Latin America and internal security and debunk Stone’s claim that the Cuban Missile Crisis had caused Kennedy to look at that region differently and decide to seek peace with Cuba and other Left movements. To conclude, I’ll consider the strange way that partisans of the idea that Kennedy was ready to leave Vietnam only revised their stories long after the president was assassinated, and then I’ll add a few ruminations about the mythology and meaning, and danger, of making JFK a hero, especially on the Left.

******

Part I

In 1991, millions of Americans plunked down their money to see Oliver Stone’s epic film JFK and today are watching and talking about his new documentary “JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass” and a new director’s cut of the original movie. President John Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK), Stone suggested, had seen the futility of the Cold War and was ready to withdraw from Vietnam and create global peace when the Central Intelligence Agency [CIA] , the Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI], the Joint Chiefs of Staff [JCS], the military, other representatives of the military-industrial complex, the intelligence bureaucracy, and even Vice-President Lyndon Johnson, fearing that his new-found pacifism was bad for business, had him assassinated.

Stone has been promoting his documentary on this topic recently, claiming that JFK was murdered by domestic enemies with renewed vigor and citing new documents that have been released since the 1990s. Kennedy was a “rebel against the establishment” and was a “warrior for peace,” Stone argues, and he challenged the military and intelligence communities as they gained bigger and bigger budgets and more power. Their interest in money and power and continued global conflict to justify their roles, “is what Kennedy understood,” the filmmaker believes, “and this is what he paid for with his life.”[1]

As the late, great muckraker Alexander Cockburn explained it years ago, Stone had bought into a right-wing view that the state was afraid of the liberal peacemaker Kennedy and had him killed on 22 November 1963, because, in Stone’s mind, “Kennedy was moving to end the Cold War and sign a nuclear treaty with the Soviets; he would not have gone to war in Southeast Asia. He was starting a back-door negotiation with Castro.” In In order to stop this new progressive American Canaan, the deep state engineered “the first coup d’etat in America.”[2]

Stone originally based this theory on the work of others, most significantly Fletcher Prouty, an officer assigned to work with the JCS, and John Newman, an Air Force veteran who also worked with the NSC. Both argued that Kennedy was a victim of what is today frequently described as “the deep state” — various intelligence and military agencies who operate the levers of the state in secret and eliminate, in many ways, people who challenge them. More recently he has gotten backup especially from David Talbot, whose book on Allen Dulles and the CIA perpetuates the theme that the deep state saw Kennedy as a threat and wanted him eliminated.[3] Others, including many ex-Kennedy officials, provided fodder for Stone with their arguments that the young president had decided to quit Vietnam, though their statements were usually made after JFK had been killed and the war had gone very wrong.

Ironically the revival of the JFK conspiracy theory, to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the release of the JFK movie, has been well-received across the political spectrum, not just by typical conspiracy theorists on the fringe. Jacobin, Counterpunch, and Majority Report, for instance, have presented discussions favorable to Stone’s documentary, while on the far right, QAnon supporters have also long believed that Kennedy was killed by the deep state, and just recently went to Dallas on the anniversary of the assassination to await the return of his late son, John F. Kennedy Jr.[4]

Stone and his allies have also stressed the release of new documents about the assassination from the Assassination Records Review Board[5], in large measure a continuing response to Stone’s allegations from the 1990s. In particular, they are contending that new information about surveillance by state agencies like the CIA, FBI, and Army against Lee Harvey Oswald has offered even more powerful, if not “smoking gun”-level, evidence of the plot against JFK. Because the new records show that various government agencies were aware of Oswald’s political leanings and whereabouts in 1963, the conspiracy theorists are convinced that dark government forces knew what Oswald was planning and did nothing to deter him.[6]

While the new documents do add detail to Oswald’s movements before 22 November 1963, various reports, including the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1978–79, had already shown that state agencies had Oswald, a public supporter of the Cuban Revolution, in their sights. The new records definitely add more detail, but do not come close to proving anything remotely like a government conspiracy to allow Oswald to kill JFK. In fact, Oswald’s political ideologies were well known long before the JFK assassination. He was on the radar already. Right now, one can purchase a “Fair Play for Cuba” pamphlet from August 1963 with Oswald’s name on it as the public New Orleans contact for the group on EBay, hardly the stuff of deep state machinations.[7] All historians want more documents declassified at a better pace, so the release of these new materials is welcome, but the does not change the story of JFK’s role in Vietnam or his assassination at all. While Stone’s supporters have been jamming social media with shrieks of “look at the new records,” once one does, there’s nothing to change what we have already known. The song remains the same.

This fascination with conspiracies and the deep state is similar to the current right-wing movement in support of Donald Trump’s lies about the election and various QAnon theories about the CIA and FBI. Though not as pernicious, Stone’s claims about various dark forces operating outside of normal bounds to rig elections, overthrow governments, and assassinate national leaders do the Left no favors. They substitute circumstantial evidence in the place of analysis and they look for heroes rather than creating resistance and organizing. Of course the CIA and other American agencies have a long record of malicious behavior, overthrowing governments abroad, assassinating foreign leaders, and repressing unions, socialists, women, African Americans, Native Americans, environmental and animal-rights activists, and other forces of liberation inside the United States. One can find that in the pages of corporate media and in public government documents. It is policy, not conspiracy. The ruling class’s behavior has been well-known for years — if it’s hiding, it’s in plain sight.

But one cannot make the leap from the fact that these groups have done horrible deeds to the conclusion that they thus killed JFK. Kennedy was one of them[8] — he firmly bought into the doctrine of containment, which he dressed up with talk of “development” and “modernization” in the Third World; he was a Cold Warrior; he invaded Cuba and contemplated a first-strike nuclear attack on Berlin within his first months in office[9]; he supported repressive Third World states per his newfound emphasis on “counterinsurgency”; he tried to overthrow Left governments abroad; he used the military to oppose national liberation movements across the globe; and he used the state to attack domestic enemies, most notably Martin Luther King (whose murderer, an illiterate drifter, was caught in London with a forged passport . . . if you’re looking for a conspiracy theory). The fascination with JFK as a young leader struck down because he was going to forge a new path away from the Cold War (and the Vietnam War more importantly) is utterly baseless and it is politically toxic, the product of nostalgia over a handsome young president who evoked images of Camelot, American exceptionalism, and innocence in the last days before racial conflict and the Vietnam War scarred the country in ways that might have been unimaginable on 20 January 1961.

The Reality of Vietnam

Stone’s conspiracy theories, his movie, and now his documentary have created great splashes in both popular culture and in the intellectual communities which study such things. Historically, however, they are nightmarish. With Vietnam as the linchpin of the thesis that JFK was killed because he was going soft on Communism and was going to end the power of the military and intelligence complexes, and specifically was going to de-escalate and withdraw troops and end the war by 1965, it becomes essential to look at Kennedy’s actual plans, policies, and actions with regard to the conflict there.

In truth, JFK, in less than three years, committed American soldiers, treasure, and credibility to the Republic of Vietnam [RVN], the American-invented state below the 17th Parallel, and dramatically enlarged the American role there. By 22 November 1963, the United States, rather than pull out, was deeply involved in the revolution-cum-civil war in Vietnam. Far from being a dove, Kennedy was the driving force behind that intervention in Indochina. His record in Vietnam, far from being a cause for the so-called deep state to want him dead, was opposite what assassination conspiracy theorists claimed that it was.

Kennedy had risen to power as a Cold Warrior and strong supporter of Joseph McCarthy and other witch hunts against alleged subversives, and the U.S. role in Vietnam from January 1961 to November 1963 continued those hardline policies upon which he had accomplished political success. The noted linguist and dissident Noam Chomsky has dissected Kennedy’s approach to Vietnam with great detail and provides overwhelming evidence that the president always sought military success in Vietnam with constantly-escalating commitments.[10] He did not waver and was not going to withdraw.

Inside Vietnam, in late 1960, the northern Vietnamese Communist Party finally agreed to organize armed resistance in the RVN, and hence the National Liberation Front (NLF) and Viet Cong (VC) were born. These groups represented a life-or-death challenge to the southern regime of Ngo Dinh Diem, who was repressive and lacked significant public support. Just weeks after the creation of the NLF, Kennedy pledged to Diem and the RVN that the U.S. would meet any new challenges with them.

As he took office on 20 January 1961, he famously pledged to “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and success of liberty.” Kennedy had run to the right of Richard Nixon in the 1960 campaign, alleging that the administration of Dwight Eisenhower had allowed a “Missile Gap” to emerge (and he had — the U.S. had about 20,000 nuclear weapons and the Soviet Union had about 1600), warned of the Soviet Union’s growth in intercontinental ballistic missiles, and pledged to increase and revitalize American nuclear forces.

Ironically, outgoing President Eisenhower, in his farewell address, had warned against the growing militarism in American society and such bellicose rhetoric, but JFK sent an opposite message. Though Kennedy had not specifically referred to Vietnam in his speech, the Diem regime could feel comfortable that their old friend would not let them down. In 1956, as a senator, Kennedy had called the RVN “the cornerstone of the free world in Asia”; it was, he admitted, “our offspring, we cannot abandon it.”[11]As president, he would not.

Vietnam had not been crucial to JFK as he entered the White House; in fact, Eisenhower had warned him that events in Laos would be more difficult in 1961. But, just months into his presidency, Kennedy was beset with challenges and failure. In Laos, he had to agree to the formation of a government which included the Communist Pathet Lao. Worse, in Cuba the U.S.- backed Bay of Pigs invasion was a fiasco. The leader of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, added to Kennedy’s woes, pledging support for wars of liberation in the Third World, refusing to remove the Berlin Wall, and treating the American president with disdain at a summer meeting in Vienna. Kennedy thus believed that he had to make a stand somewhere — “that son of a bitch won’t pay any attention to words, he has to see you move,” he told reporters — so why not Vietnam? Walt Whitman Rostow, one of his closest advisors, suggested that “clean-cut success in Vietnam” could erase the stain of disaster from the Bay of Pigs. In Saigon, the head of the American Military Assistance Advisory Group [MAAG], General Lionel McGarr, likewise noted the “strong determination” in the White House to stop the “deterioration of US prestige” in April 1961.[12]

Thus JFK, if not desperate at least anxious for a Cold War success, began to increase significantly the U.S. commitment to the RVN and prepare to conduct an aggressive war there. In January, he authorized the Counterinsurgency Plan for southern Vietnam, which called for training the southern army in anti-guerrilla tactics, not just conventional warfare. He then approved expanding the Army of the RVN [ARVN] by 20,000 troops, to 170,000, and then by another 30,000, while enlarging the Civil Guard from 32,000 to 68,000 troops. To pay for these reinforcements, the White House sent Diem an additional $42 million in 1961, on top of the $225 million per year he was receiving already. And in May, Kennedy sent Vice-President Lyndon B. Johnson [LBJ] to Vietnam as a public relations measure. While in Saigon, the Vice President told the media that Diem was “the Winston Churchill of Southeast Asia,” though he privately laughed later that “shit, man, he’s the only boy we got out there.”[13]

Recognition of Diem’s repression and America’s limited choices did not deter the White House. Indeed, JFK refused to even talk with Ho Chi Minh or the NLF, warning that negotiations would make him look weak: “If we postpone action in Viet-Nam to engage in talks with the Communists, we can surely count on a major crisis of nerve in Viet-Nam and throughout Southeast Asia. The image of U.S. unwillingness to confront Communism — induced by the Laos performance — will be . . . definitely confirmed. There will be panic and disarray.” To the president, American credibility — appearing strong against Communist advance — would thus be a major factor driving his Indochina policy, and he would not back down. Nor would his Secretary of Defense, Robert Strange McNamara, who informed military officials that the administration “had made the decision to pursue the Vietnam affair with vigor and that all reasonable amounts of resources could be placed at the disposal of the commanders in the area.”[14]

And so, in 1962, it was done. In January, a new commander, Paul D. Harkins, arrived in Vietnam convinced that America’s technological superiority would reverse conditions there. The war was going badly, with the NLF’s political influence growing and the armed wing of the insurgency, the VC, holding the military initiative. To Harkins, and the White House, American tanks and aircraft could be used to flush out the VC and destroy them. In 1962, then, JFK went big and deployed Army helicopter companies, fixed-wing aircraft, a troop carrier squadron, reconnaissance planes, air controllers, crop defoliants to destroy the VC’s jungle cover, Navy mine sweepers, CS gas and napalm — a gasoline gel that seared human flesh. He also authorized the development of strategic hamlets in the RVN — a disastrous program in which Vietnamese peasants were removed from their homes and possessions and relocated to allegedly safe hamlets where they would be protected from the NLF, but which in fact alienated even more villagers from the government and helped VC recruiting efforts.

At the same time, the number of U.S. “Advisors” in Vietnam, 800 in January 1961, rose to 3400 in April 1962 and over 11,000 by the end of the year, and would go up again to 16,700 by the time of Kennedy’s assassination. The ARVN grew again too, to 219,000, while the Civil Guard increased to 77,000. That level of commitment and the introduction of American firepower had the desired impact. The VC fled in horror as U.S.- provided weapons and ammunition rained down on them. As Harkins put it, the napalm “really puts the fear of God into the Viet Cong . . . and that is what counts.” McNamara was similarly pleased with the “tremendous progress” in 1962, and the American commander was assuring him that “there is no doubt we are on the winning side.”[15]

As the evidence made clear, Kennedy was deeply committed to success in Vietnam with heavy firepower and a growing commitment, and believed that he had gained the upper hand in Indochina in 1962. The administration was so flush with success and optimistic that the war would be over quickly, in fact, that it later approved the withdrawal of 1000 American troops (a point Stone would later use to argue that JFK was souring on and planning to get out of Vietnam).

Breakdown 1963: The Coup and “I think we should stay”

The optimism of 1962 was short-lived. On 2 January 1963, the VC routed the ARVN, even though it had a 4 to 1 troop advantage, artillery, armor, and helicopters, at the village of Ap Bac, 35 miles southwest of Saigon in the Mekong. The enemy struck, eluded the southern army, and struck again, killing three Americans and downing five helicopters in the process. ARVN commanders, under orders from Diem not to lose troops, did not force their men to fight and so allowed the VC to take the initiative and then escape from Ap Bac. For the NLF, the battle marked a turnaround from the previous year, and its prospects would improve throughout the next twelve months, while Diem’s took a corresponding downturn, militarily and politically.

There was grave internal crisis in 1963 as well, particularly religious turmoil. The Ngo family had favored Catholics in administrative and military matters since 1954 and began to repress the majority Buddhists — which they saw, with reason, as a political enemy — more intensely in the spring, forbidding them from celebrating Buddha’s birthday and even sending troops into their temples to attack and kill the faithful. Then, on 10 June, the monk Quang Duc famously sat down in the middle of a busy Saigon street, doused himself with gasoline, and lit himself on fire to protest Diemist repression.

International media, tipped off by the Buddhists, was there and Quang Duc’s story and photo were front page news worldwide. For his part, Diem continued to strike at the Buddhists. After nearly a decade of supporting the RVN and the Ngos, it was finally clear that Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu were beyond rehabilitation. The United States, which had followed a policy of “sink or swim with Ngo Dinh Diem,” finally agreed he had to go.

RVN Generals launched a coup against Diem and Nhu on 1 November, deposing and murdering them in a van rather than allowing them to flee to Paris. While there is abundant evidence of Kennedy’s commitment to escalate the war in Vietnam to achieve success from early 1961 onward, Stone and others argue that by later 1963 he had developed strong misgivings and was prepared to withdraw, thus prompting dark forces in the intelligence and military communities to assassinate him. With that in mind, then, the U.S. role in the coup against Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu is a critical piece in debunking Stone’s argument about Kennedy. The coup took place just three weeks before Kennedy himself was killed, so the president’s role in deposing the Ngos offers overwhelming evidence that JFK or other government officials were doubling down in Vietnam, not preparing to get out.

JFK himself had been critical to Diem coming to power and the U.S. inventing the RVN and subsequently sending immense funding and weapons to southern Vietnam — and he was immersed in the deliberations over what to do about Diem in the autumn of 1963, that pivotal point where Stone claims Kennedy was making plans to withdraw from Vietnam. Indeed, even before deliberations over ousting Diem became organized, the White House began to express its concerns over instability in the RVN due to Diem’s repression and in a 9 July briefing with the Director of Central Intelligence, CIA officials told the White House that “South Vietnam continues restive over the unresolved Buddhist issue and a coup attempt is increasingly likely,” that the ARVN Commander Tran Van Don had told CIA officers that military was planning to overthrow Diem and Buddhist leaders were becoming more engaged in anti-Diem struggle, and that RVN officials were blaming anti-regime activity on the American media for its reporting on the Buddhist protests and Diem’s corruption and repression in general.[16]

By late August the crisis in the RVN was much more grave and in a meeting to discuss the well-known “Hilsman Cable,” an important document in which Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs Roger Hilsman had laid out in bleak terms a situation in the RVN that was “pretty horrible to contemplate.” The U.S. government, Kennedy’s main military and diplomatic officials agreed, “cannot tolerate [a] situation in which power lies in Nhu’s hands,” especially after another series of pagoda raids he had just directed. “Diem must be given [a] chance to rid himself of Nhu and his coterie and replace them with best military and political personalities available,” but if “Diem remains obdurate and refuses, then we must face the possibility that Diem himself cannot be preserved.” Officials in Saigon and Washington who were in contact with RVN military officials opposed to the Ngos were also directed to tell potential coup-planners in southern Vietnam that “we will give them direct support in any interim period of breakdown [of the] central government mechanism.”[17]

Just days later, JFK discussed the Hilsman cable with his national security officials. Kennedy began, “if we’re unsuccessful here, and these [RVN] generals don’t do anything, then we have to deal with Diem as he is . . . Then the question, what do we do to protect our own prestige and also to make it — see if we can have this thing continue on successfully?” Hilsman, like most U.S. officials, believed Nhu, not Diem, was the key problem and that he was “basically anti-American” and showed signs of “emotional unstability [sic].” To Hilsman it was “most important” to recognize that key elements in the southern government and the army were abandoning Diem in the wake of the Buddhist uprisings and that “the situation will rapidly worsen.” Secretary of State Dean Rusk said much the same, adding that “we’re on the road to disaster” and the U.S. could “take it by our choice, or be driven out by a complete deterioration of the situation in Vietnam, or move in such [U.S.] forces as would involve our taking over the country”[18]

After hearing such bleak appraisals, Kennedy suggested talking with McNamara, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, and Harkins to get their views, and JFK was already considering removing Diem and his brother — ”I don’t think we ought to let the coup . . . maybe they know about it, maybe the [RVN] generals are going to have to run [the Ngos] out of the country; maybe we’re going to have to help them get out of there.” Kennedy remained cautious, advising to defer action on a coup “unless we think we got a good chance of success.” The president concluded “we’re not really in a position to withdraw” [my emphasis] so he would rely on Lodge and Harkins to advise him on whether to go forward with the action against Diem and Nhu. But ultimately, the administration was on board, with JKF, Secretary of State Dean Rusk (who said that if JFK signed off he would give “a green light too”), Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric, and General Maxwell Taylor, chair of the JCS, all signing off on the hard-line recommendations.[19] There is no evidence that Kennedy was reconsidering his commitment to war in Vietnam. Indeed, the opposite was the case.

In fact, at that very same time Rusk reported that the U.S. was prepared to supply RVN military coup-planners in the field with arms, ammunition, and logistical support, Kennedy ordered his advisors to compile a list of potential successors should the ouster take place. Rusk made it clear what was at stake, admitting that if a coup failed the U.S. would be “on an inevitable road to disaster. The decision for the United States would be . . . to get out and let the country go to the Communists or to move U.S. combat forces into South Viet-Nam and put in a government of our choosing.” So JFK, like everyone else, knew exactly what was in play regarding the potential coup against Diem, and made no move to stop it, for the memorandum ended with the statement that “there was no dissent from the Secretary’s analysis.”[20]

Already, in late August, American planning to oust Diem and Nhu was well underway with the president’s support, a far cry from Stone’s argument that Kennedy was ready to withdraw from the war. It was clear, as diplomatic and military officials in southern Vietnam had reported “that the war against the Viet Cong in Vietnam cannot be won under the Diem regime,” and at a 29 August meeting at which Lodge and Harkins reported that JFK asked if anyone had reservations about the current campaign of seeking alternatives to Diem and Nhu, the president answered his own query by asserting that “if Diem says no to a change in government there would be no way in which we could withdraw our demand.” The White House, quite clearly, had drawn a line in the sand and the Ngos had to either change dramatically and enact serious reforms or they would be ousted.

Toward that end, the he offered a summary of actions to be taken which included Harkins and the CIA approaching southern generals about a coup; authorizing Lodge to announce a suspension of U.S. aid to the RVN when the time was right according to the White House; making no announcement of any movement of U.S. forces to the area in support of a coup; and giving Lodge authority over all operations to get rid of Diem and Nhu, overt and covert. At another meeting on Vietnam later that day, McNamara urged a final overture to Diem because he doubted any successor government could run the country, to which, according to the minutes of the meeting, “the president asks who runs it now; that it seemed to him it was not being run very well.”[21]

The positions taken and decisions made in late August regarding the U.S. determination to eliminate Diem and Nhu were made with a clear goal of regaining some initiative in the RVN and stalling what American officials recognized as an inevitable march to victory by the NLF and VC in the south. There was no idea given to leaving Vietnam. In fact, in two important interviews with TV anchors Walter Cronkite and Chet Huntley just shortly before his own death, Kennedy doubled down on his commitment to Vietnam.

While Stone and others have cited the interviews where JFK admitted that the situation in Vietnam was going badly, they left out key parts that attested to the president’s resolve. During a 2 September interview with Cronkite, the president said that it was the RVN’s war to win or lose and that “all we can do is help,” but did not “agree with those who say we should withdraw. That would be a great mistake. I know people don’t like to see Americans to be engaged in this kind of effort… But it is a very important struggle even though it is far away.” A week later he told Huntley essentially the same thing. Although Americans would get anxious or impatient about Vietnam, “withdrawal only makes it easy for the Communist. I think we should stay.”[22]

At the same time Kennedy was publicly reaffirming the U.S. commitment to Vietnam, the president sent McNamara and Taylor to Vietnam to appraise the situation there. Their report formed the basis of National Security Action Memorandum [NSAM] 263, which Stone and the Kennedy conspiracy cult have cited as their smoking gun to show JFK was ready to leave Vietnam. Like the rest of the Stone theory, this episode has been misrepresented to make a claim opposite of the truth. In Vietnam, McNamara and Taylor heard Harkins talk of the “great progress” in the war there and came back and told the president that he should publicly report that he was going to withdraw 1000 military personnel and anticipated the bulk of American troops could be phased out by the end of 1965. Even so, the White House issued a statement again making clear its support of the commitment to the RVN.[23]

On October 11 Kennedy then authorized NSAM 263, which approved of the McNamara-Taylor recommendations to withdraw 1000 troops, though not publicly announce it, and said a “major part” of military tasks can be done by end of 1965, or 24 months in the future. The Americans continued to insist that South Vietnam improve its military performance, and stressed that the U.S. would have to emphasize training the Vietnamese to take over “essential functions” of warfare by late 1965. In other words, NSAM 263 continued the U.S. approach to Vietnam that had been in effect the entire Kennedy presidency, as it remained the “central object” of the U.S. in South Vietnam “to assist the people and Government of that country to win their contest against the externally directed and supported Communist conspiracy. The test of all decisions and U.S. actions in actions in this area should be the effectiveness of their contributions to this purpose.”[24]

Rather than a striking break from the U.S. war in Vietnam that would indicate a change of heart by JFK, NSAM 263 was a continuation of the American doctrine in the Cold War from the end of World War II forward. It was essentially a restatement of the Truman Doctrine and NSC-68, yet Stone and his followers created a myth to substitute for the obvious reality and have convinced huge numbers to believe it. In fact, even after the assassination, U.S. policy in Vietnam remained the same. (And, just a few days after the assassination, Lyndon Johnson signed off on NSAM 273, which had been prepared under Kennedy and, again, emphasized that America’s “central objective” in Vietnam was still to take the actions necessary to prevent Communist victory in the south.)[25]

So the evidence of Kennedy’s continued commitment to the war in Vietnam was overwhelming as the coup planning continued. In late October, in two of the later meetings regarding a potential coup, the State Department and National Security Council produced separate check-lists of possible actions in the event of an overthrow of Diem. All the options involved deep U.S. involvement and all were based on the high likelihood, if not certainty, of a coup attempt.[26]

On the morning of 1 November, as the coup in Saigon began to unfold, Kennedy again met with his advisors. Rusk was concerned that the U.S. get the support of the RVN’s vice-president so “the façade of constitutionalism would thus be preserved.” Kennedy himself did not suggest regret about the coup (though by all accounts he was aghast that Diem and Nhu were murdered) and stressed that all officials publicly deny any role in the ouster of the Ngos. Strikingly, he was concerned with public relations, that he and his advisors might have to reconcile supporting this coup against an ally in the RVN and recognizing a new government after recently refusing to recognize a rebel government which had overthrown the government in Honduras, and he directed that a paper on the topic be prepared “so that everyone in the government would be saying the same thing in response to this question.”[27]

JFK himself would be assassinated 3 weeks later in Dallas, but there is no reason for the so-called deep state to have wanted him dead because he was trying to get out of Vietnam and usher in a new era of global peace. In a speech early on 22 November in Fort Worth, Kennedy admitted that “without the United States, South Vietnam would collapse overnight.” Much more telling were the remarks he was scheduled to deliver at the Dallas Trade Mart that evening. The entire document in bellicose and unwavering, and it should be read in full to get a real sense of where JFK’s foreign policy ideas stood at the moment he was allegedly targeted by the military and intelligence complexes for being a dove. Kennedy’s speech both boasted and warned enemies of American strength.

“In this administration,” he said firmly, “it has been necessary at times to issue specific warnings — warnings that we could not stand by and watch the Communists conquer Laos by force, or intervene in the Congo, or swallow West Berlin, or maintain offensive missiles on Cuba. But while our goals were at least temporarily obtained in these and other instances, our successful defense of freedom was due not to the words we used, but to the strength we stood ready to use on behalf of the principles we stand ready to defend.” He added that his administration had increased the number of Polaris submarines by 50 percent, the Minuteman Missile purchase program by 75 percent, raised the number of strategic bombers on 15 minute alert by 50 percent, increased the total number of nuclear weapons available in strategic alert forces by 100 percent, and raised the level of tactical nuclear forces deployed in Western Europe by 60 percent.

The U.S., he also boasted, raised the number of combat-ready army divisions by 45 percent, and had doubled the number of tactical aircraft, while ship construction and army procurement of materiel had also risen by 100 percent. In finishing his laundry list of the vast military build-up, he pointed out that he had increased special forces by nearly 600 percent, and those new troops “are prepared to work with our allies and friends against the guerrillas, saboteurs, insurgents, and assassins who threaten freedom in less direct but equally dangerous manner.” Finally, Kennedy detailed the aid that the U.S. was giving to other nations to fight against Communism and pointed out that “our assistance to these nations can be painful, risky and costly, as is true in Southeast Asia today. But we dare not weary of the task.”[28]

Part II

Civilian Hawks and Military “Doves”

A centerpiece of the JFK conspiracy theory is that the military wanted Kennedy gone because it wanted to be unleashed to fight in Vietnam. Kennedy’s actions as president, however, up to his role the anti-Diem coup just weeks before his own assassination, offer overwhelming evidence that the president was committed to a military solution in Vietnam with an ever-escalating presence, and it powerfully debunks Stone’s argument. But there are more firm reasons to refute the filmmaker’s theory about Kennedy withdrawing from Vietnam and ending the Cold War, and thus prompting the military-industrial complex and others to have him killed. In reality, the U.S. military was far more “dovish” on Vietnam than Kennedy and his civilian advisors. There would be no motive to want to harm Kennedy because he was going soft on Vietnam, because the military itself was never eager to fight there.

In the early 1950s, leading military officials from all the services had time and again voiced their reluctance to fight in Vietnam, including Generals Matthew Ridgway and James Gavin, General and later Ambassador Saigon J. Lawton Collins, and others. During the Kennedy years, the military’s opposition was not as pronounced, but it stood in juxtaposition to JFK’s hawkish approach to Vietnam. From 1961 to 1963 the military was variously ambivalent, critical, or even internally contradictory with regard to Vietnam. Leading officers might not have opposed war as strongly as their predecessors a decade earlier, but neither did ranking military figures — including CINCPAC Admiral Harry D. Felt, General McGarr, and Marine Commandant David M. Shoup, and even Maxwell Taylor — behave according to the hawkish caricature that many liberal critics have developed over the years.[29]

Most officers in Washington and Saigon in fact tended to be critics of the war or were aware of the political stakes in taking on the president so did not challenge him directly but did recognize the perilous situation in Vietnam. Most were never eager for combat, understood the obstacles to success, and were aware of the domestic political implications of warfare in Indochina, yet within two-and-a-half years, as Kennedy intensified the war in Vietnam, they had to put their reluctance to intervene on the backburner and began to pursue a military solution in Vietnam per JFK’s plans. Although they followed Kennedy’s lead, military officials — some of whom, like Generals Gavin and Maxwell Taylor, had campaigned for JFK and received posts in his administration — recognized that U S prospects in Vietnam were always uncertain and that American combat role would not ensure success and should be avoided. By November 1963 then, the U.S. military, obedient if not in concert with Kennedy’s political objectives, was involved in a war in Vietnam that would serve neither U.S. nor Vietnamese interests.

As he took office, Kennedy had a strong relationship with the military and had begun to make good on promises to give it more assets and bigger budgets. The brass certainly appreciated the money but did not share Kennedy’s enthusiasm for involvement in Vietnam. The heads of the Air Force and Navy, which would fight at a distance and take far fewer casualties, were willing to consider a military role in Indochina, but they were not a majority. More typically, Marine Commandant David Shoup rejected calls for intervention while the Army Chief of Staff, General George Decker, thought that “there was no good place to fight” in Southeast Asia. [30]

The commander of U.S. forces in the Pacific, Admiral Harry D. Felt, was also “strongly opposed” to troop deployments, especially because he anticipated that the ARVN would fight even less if American troops were there to bail them out. Felt, like most officers, believed that the United States should limit its role to training and supplying the south Vietnamese military to take on the VC by themselves [what would become “Vietnamization” when Richard Nixon was president]. Perhaps no officer received as much publicity for his criticism as Colonel John Paul Vann, whose leaks to the New York Times revealed that the ARVN was avoiding battle and that the heavy use of American firepower and air strikes was killing huge numbers of civilian villagers — the very people that the Americans were trying to “save” — throughout the South. As one Army report from 1962 concluded, “the military and political situation in South Vietnam can be aptly described by four words, ‘it is a mess.’”[31]

As the Kennedy administration sent more resources and money into Vietnam, the military went along with Kennedy but continued to express conflicting views about Vietnam policy. Military officials generally supported Kennedy, especially after he replaced holdover brass with his own generals and because he put forward budgets with a projected increase for the Pentagon of $17 billion over five years. Optimism also grew within the military, as we have seen, with Paul Harkins’s arrival and the introduction of technological warfare and helicopters, among other resources, and even critics of the war fell in line as money flooded into the military and resources poured into Vietnam. However, U.S. officers continued to recognize that the Viet Cong was stronger and committed to conducting long-term, attritional warfare that could not be defeated with a conventional military response.

They also continued to lament the incessant political repression and chaos in Saigon which ultimately led to the Diem coup, and in the case of John Paul Vann and others pointed out the politicization and shortcomings of the South Vietnamese military forces. And, whatever their opinion of the wisdom or risks of intervention, virtually every American military official assumed during this time that the United States would not even contemplate sending combat forces into battle in southern Vietnam. The military had to take its cues from Kennedy, who was preparing to go all-in in Indochina over its the reservations, reluctance, or at times opposition. Stone’s position that the military feared or hated JFK enough to plot to kill him is absurd on the surface, but even more irrational, if not risible, when viewed within the context of how the military really felt about Vietnam and JFK.

Even more telling is that the military’s pessimistic evaluations and often-cautious recommendations essentially hardened after the assassination. If the military wanted Kennedy out of the way so it could go all-out against the Revolution in Vietnam, then ranking officers would have been sending along sanguine reports and urging a full-on war. Yet, Throughout 1964 and 1965, as the Johnson administration repeatedly escalated the war in Vietnam, the military remained unconvinced of the need for or value of intervention. Indeed, both Generals Taylor and William Westmoreland, the ambassador and commander who are remembered as hawks on Vietnam (indeed, some vets derided the commander as “General Waste-more-men”), strongly opposed the introduction of combat troops in the crucial 1964–65 period, as did ranking officers in every service.

In an address at Marine headquarters in late 1963 the incoming Commandant, General Wallace M. Greene, Jr., explicitly rejected American participation in the war in Indochina, lamenting that “we’re up to our knees in the quagmire [in Vietnam] and we don’t seem to be able to do much about it.” Greene hoped that the current Marine presence in Vietnam, about 550 troops, would remain low. “Frankly, in the Marine Corps we do not want to get any more involved in South Vietnam because if we do we cannot execute our primary mission,” he admitted. With more important commitments elsewhere, he feared that the Corps would be overextended in Vietnam. “You see what happened to the French,” Greene ruminated, “well, maybe the same thing is going to happen to us.” Generals Victor Krulak, who was assuming command of the Fleet Marine Force, Pacific [FMFPac], and Donald Bennett, director of strategic planning for the Army, had similar reservations about expanding the U.S. role in Vietnam, with Bennett later charging that “certainly from September of [19]63 on, the forcing [into war in Vietnam], as far as I could tell, came from the civilian side.”[32]

To Taylor, it was neither “reasonable or feasible” to expect Caucasian American soldiers to take on the duties of Asian guerrilla warfare. As soon as American troops entered the RVN, the Vietnamese would “seek to unload other ground force tasks upon us” and would perform even “worse in a mood of relaxation at passing the Viet Cong burden to the U.S.” Taylor even went so far as to suggest that LBJ reduce the U.S. role to sending in advisors, or maybe even “disengage and let the [RVN] stand alone.”[33]

Westmoreland was likewise reluctant to fight in Vietnam. In September 1964, the commander “did not contemplate” putting U.S. troops into combat; that “would be a mistake,” he told Taylor, because “it is the Vietnamese’s war.” In late 1964, again insisting that “a purely military solution is not possible,” Westmoreland did not even mention using ground troops in his reports to Washington. In probably his most prophetic analysis, in January 1965, just ten weeks before the introduction of combat troops at Da Nang, he and his staff urged a continuation of the flawed advisory system, but no combat troops. The United States, they recognized, had spent vast amounts of time and money to develop the ARVN, with little luck, and “if that effort has not succeeded, there is even less reason to think that U.S. combat forces would have the desired effect.” The involvement of American troops in the RVN, the military staff in Saigon concluded, quite amazingly, “would at best buy time and would lead to ever increasing commitments until, like the French, we would be occupying an essentially hostile foreign country.”[34]

More than a year after JFK’s assassination, then, the military, which Stone and others would want people to believe plotted to have the president killed because of his reluctance to fight in Vietnam, were continuing to be far more hesitant and pessimistic about the war than the civilians were. . . .

Beyond Vietnam: Kennedy’s Record of Aggression and Intervention

National Security Policies

There are some who have argued that the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 tempered Kennedy and made him more dovish, and they point to the establishment of the hotline between Washington and Moscow, and, even more, the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty to suggest that JFK was moving to dramatically deescalate and eventually end the Cold War. Kennedy did in fact take measures to reduce tensions between the Soviet Union and United States, but the idea that he was becoming so dovish that state agents had him assassinated is preposterous and without evidence.

To Stone, the alarming events of October 1962 caused JFK to take a hard line against the Soviet installation of missile sites in Cuba which ultimately forced Khrushchev to back down, and was “the greatest single act of human courage the world ever witnessed with that much at stake.”[35] More to the point, Stone and other partisans of the conspiracy to kill Kennedy believed that the crisis made the president realize how dangerous nuclear weapons were and thus reappraise life-long held beliefs about the Cold War and global conflict.

Yet Stone also contends, contradictorily, that suspicions arose that Kennedy was “soft on communism” because he failed to use military force in October 1962. In any event, Kennedy in truth took a hard line, imposing a blockade on Soviet ships that could have led to armed conflict or even a nuclear exchange. And the American people saw it that way, with 82 percent saying U.S. power had increased after the missile crisis, while 70 percent had a favorable view of his foreign policies, and 74 percent believed he would be reelected in 1964.

So, in truth, Kennedy’s political position had improved by late 1962, and in fact he did use that momentum to take some important measures with regard to the Soviet Union. In early 1963, the president established a hot line (a teletype machine, not a “red telephone”) to provide instant communication between Washington and Moscow in the event of conflict or emergency, and, more importantly, convinced congress to pass a Limited Nuclear Test Ban treaty in September 1963, which prohibited nuclear tests under water, in the atmosphere, and in outer space, and pledged all signatories to end the arms race.

But even this particular accomplishment was not indicative of any change of heart by Kennedy. JFK had been advocating a nuclear test ban since his days as a senator in the mid-1950s, and it had strong support in both parties by January 1961. Indeed, the final vote on the treaty was 80–19, so the idea that the military or intelligence communities were so angry that they would try to assassinate JFK over this issue (which was of the same nature as Eisenhower’s pursuit of the Open Skies Treay in 1955 anyway) is, again, without evidence or merit.[36] Indeed, in the period between making the agreement with Khrushchev and holding the senate vote, a large and diverse group of political figures publicly supported the test ban — officials from the Atomic Energy Commission, prominent Republicans like Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, and Everett Dirksen, former President Harry S. Truman, and various labor and church groups. Over 60 percent of Americans supported the treaty, while less than 20 percent opposed it.[37]

Most importantly, even the JCS supported the nuclear test ban. In the first deliberations about the treaty, the chiefs were reluctant to agree to limiting nuclear testing, but began to soften their positions in July, after Kennedy assured them that “we cannot reduce our military readiness if an accord is reached, for the whole situation could turn around in six months.” Feeling less apprehensive, the JCS consulted with CIA Director John McCone, AEC Chair Glenn Seaborg, various nuclear physicists, and other scientific and political officials. Their answers, according to the official history of the period “plainly eased JCS concerns.” Even hawkish Air Force Chief of Staff Curtis LeMay, who wanted the U.S. to develop a 100 megaton bomb to match the Soviet Union’s “Tsar Bomba,” knew that it would be to U.S. “political disadvantage” if it did not ratify the treaty. McNamara, the chiefs’ civilian boss, sent them a draft endorsing the treaty and recommending ratification, and in mid-August the JCS abandoned its reservations. Overall, the JCS said, “the US at present is clearly ahead of the USSR in the ability to wage strategic nuclear war, and is probably ahead in the ability to wage tactical nuclear war.” Ultimately, the Chiefs concluded that the treaty was “compatible with the security interests of the US” and supported its ratification.[38]

Kennedy’s national security policy, the record indicates, was consistent throughout his presidency, both before and after October 1962, and it was aggressive and based on military strength. In June 1962, the Policy Planning Council prepared a draft of the U.S. Basic National Security Policy that was complete with boilerplate Cold War analyses and recommendations. It began by reiterating that “now and for the foreseeable future U.S. military policy is a crucial determinant of the fate of the free community because our military strength is proportionately great in relation to our population and command over resources, and because the security of our allies is intimately dependent on our strength and will to exercise it.”

The planners behind the report did not anticipate that the Soviets would take any aggressive actions abroad (this was pre-missile crisis) but also were committed to keeping the U.S. military deployed abroad and well-funded in the event some crisis with the USSR did emerge. The report also discussed what the U.S. perceived as the Soviet threat in some measure and was open to changing the U.S. “no first strike” with nuclear weapons policy in the event war broke out. It also discussed America’s need not just for nuclear arms but also chemical and biological weapons, urged an increased commitment to supporting American allies and having adequate funding and production for U.S. military materiel at home, and said that the U.S. had to “be prepared to fight locally in direct conflict with Sino-Soviet forces.”[39]

In early 1963, as the dust settled after the missile crisis, JFK did not shift policies, but continued his aggressive and militarist approach, in rhetoric and action. In his State of the Union Address, the president continued to argue for a hardline against U.S. enemies. He could “foresee no spectacular reversal in Communist methods or goals,” but would be open to peace overtures from Moscow. However, until Khrushchev made that choice, “the free peoples have no choice but to keep their arms nearby.” Accordingly, Kennedy promised “the best defense in the world,” which meant a rising defense budget because there was no “bargain basement” way to achieve security.

In 1963, that would mean spending $15 billion on nuclear weapons systems alone, “a sum which is about equal to the combined defense budgets of our European Allies.” In addition, JFK pledged improved air and missile defense systems, improved civil defense, a strengthened anti-guerrilla capacity, and “of prime importance” — more powerful and flexible non-nuclear forces (part of so-called “flexible response).[40] In less than three years as president, Kennedy and McNamara oversaw one of the largest increases in military spending in non-wartime conditions in U.S. history.[41]

Around this time he also proposed the establishment of the Multilateral Nuclear Force (MLF), which would put integrated North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO] forces together on nuclear submarines and ships, and, most controversially, include personnel from West Germany to have partial control over nuclear weapons, less than two decades after the end of World War II. The Soviet Union, not surprisingly, was outraged by the idea of giving the Germans authorization over nuclear weapons and believed that Kennedy was making nuclear proliferation more likely. Though the U.S. had drafted a Non-Proliferation Treaty in early 1963, the MLF, as Khrushchev saw it, was exacerbating European instability, not limiting it.[42]

In fact, JFK supported the MLF even though one of America’s key allies, France, opposed it. “Our interest,” Kennedy said at an NSC meeting in January 1963, “is to strengthen the NATO multilateral force concept, even though de Gaulle is opposed, because a multilateral force will increase our influence in Europe and provide a way to guide NATO and keep it strong. We have to live with de Gaulle” (who was causing problems that “are not crucial in the sense that our problems in Latin America are”). At that same NSC meeting, Kennedy pointed out that one of “our big tasks” would be to persuade the Europeans to increase their defense forces. JFK, more than his predecessors, was also willing to assert American power and act unilaterally with regard to Europe and NATO. Kennedy did not believe that the “approval of the alliance was a condition that pressed on him.”[43]

“If we are to keep six divisions in Europe, the European states must do more,” he said. “Our forces in Europe are further forward than the troops of de Gaulle who, instead of committing his divisions to NATO, is banking on us to defend him by maintaining our present military position in Europe. While recognizing the military interests of the Free World, we should consider very hard the narrower interests of the United States.” [44] Once again, JFK was hardly going soft as a result of the nuclear crisis a few months earlier in Cuba. The MLF never became a reality, but Kennedy’s determination to expand Europe’s nuclear capability, with ex-Nazis involved in operational control of NATO weapons, showed his true colors. The president also showed his commitment to Germany, and his continued Cold War bona fides, during a visit to the wall in West Berlin in June, as his words assured the West Germans that they could rely on the U.S. for their security and condemned communism. “There are some who say that communism is the wave of the future . . . And there are some who say in Europe and elsewhere we can work with the Communists . . . And there are even a few who say that it is true that communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress,” and Kennedy admonished them, “let them come to Berlin” and finished with his famous declaration “Ich bin ein Berliner,” or “I am a Berliner.”[45]

Late into the year, even as Kennedy, in NSAM 270, announced the redeployment of some personnel and units from Europe, the U.S. still was keeping six ground divisions in Germany “as long as they are required.”[46] Even with the drawdown of some units and equipment, the U.S. was not withdrawing from Europe, as Dean Rusk made clear in an address in Frankfort at the very same time as NSAM 270 was authorized. “When we say that your defense is our defense,” he assured the Germans, “we mean it. We have proved it in the past [and] will continue to demonstrate it in the future. We have six divisions in Germany. We intend to maintain these divisions here as long as there is need for them — and under present circumstances there is no doubt that they will continue to be needed.” Rusk also stressed that U.S. had established “the world’s largest logistical system” in Germany which kept forces in the “highest state of readiness with the most modern and powerful equipment . . . . and they are backed by nuclear forces of almost unimaginable power.” Finally, Rusk reminded the Germans that the U.S. had 2.7 million active troops, with about 1 million outside the U.S. and would maintain security not just in Europe but worldwide with its power.[47]

JFK’s national security policies, from his time in the senate until the end of his life, were based on traditional concepts of power, containment, and nuclear superiority. Even as he agreed to a limited test ban, he was always sure to maintain vast American superiority and flex military strength if needed. There is nothing in the record to indicate that Kennedy had any plans that would fundamentally shift U.S. cold war doctrine and there was simply no reason for the military to have any deep conflict with him, let alone reason enough to want him killed. Again, Stone’s argument fails in the face of overwhelming evidence.

Part III

Latin America and Internal Security

Kennedy’s supporters point to his approach to the so-called Third World to assert he was charting a new path on foreign policy. JFK was familiar with the work of revolutionaries like Mao Zedong and understood that the social conditions in poverty-ridden, underdeveloped countries often led to communist success, both in organizing communities and in politics, and he was aware that Khrushchev had vowed to support wars of national liberation, creating more problems in parts of the world where western states had occupied an imperial role for decades or more. So Kennedy would help those places where the Left was growing with an alternative path to progress — the key ideology would be “modernization” and the centerpiece program would be The Alliance for Progress.

Modernization had been an increasingly popular idea among liberals in the Kennedy era, especially associated with Walt Rostow’s The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Modernization would use the lure of development and reform, rather than intervention and repression, to create better and more equitable societies in the Third World and thus make communism unappealing to the masses. The U.S. had tried out such ideas in other forms before, during the days of “Dollar Diplomacy” or with the “Good Neighbor Policy” for instance, but this would be more nuanced and much bigger, with the Alliance for Progress as its showpiece program. In reality, Kennedy’s policy would not be a departure from America’s past in that region and would, again, be based on militarization rather than modernization. JFK would support authoritarian regimes, exert diplomatic and economic inducements and threats, subvert Left movements and governments, and use American military forces to change the internal structure of other states.

Kennedy’s words about U.S. options in the Dominican Republic after its dictator Rafael Trujillo was murdered have often been quoted because they sum up his views so well — “there are three possibilities in descending order of preference: a decent democratic regime, a continuation of the Trujillo regime, or a Castro regime. We ought to aim at the first but we cannot renounce the second until we are sure we can avoid the third.”[48] Of course, in his first 100 days Kennedy tried to “avoid” the third option at the Bay of Pigs, which was a spectacular failure. But moving onward, JFK, Stone’s dove who was going to thaw relations with Cuba after the missile crisis and renounce America’s imperial past, continued long-standing U.S. policies.

The main Kennedy-era document on Latin American internal security was NSAM 134, adopted in early 1962. It was full of typical Cold War condemnations of communism and the Left, which was using “now-familiar techniques of pressure, infiltration, and division in weakening the will of governments for taking effective action, and of initiating violence principally in rural areas and on issues where internal security forces are vulnerable.” It provided a laundry list of areas where local U.S.-allied governments faced “critical problems in internal security” exacerbated by political and class divisions — Colombia and Bolivia, which required urgent attention; Peru and Ecuador, which were on the edge of crisis; and Venzuela, Brazil, and Argentina, which risked sudden deterioration.[49] Of course there was no need to mention Cuba, where the U.S. imposed a brutal embargo in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion and continued to do so post Missile Crisis and had been trying to assassinate Fidel Castro, as chronicled by the Church and Pike Committees.[50]

Despite the rhetoric of modernization and the public relations hype of the Alliance for Progress, the U.S. was still going to rely on force to ensure its interests in Latin America, increasing the American Military Assistance Program, supporting and training military forces in that region, and developing local forces to not just fight conventional warfare but also to meet the challenge of internal subversive movements of the Left. And, counter to Stone’s claim that JFK was going to thaw relations with Cuba, JFK’s pressure on the island did not abate and Castro was cited as the justification for the use of force in Latin America in virtually every statement and document produced by diplomatic and military officials.[51]

Post-Missile Crisis, the time when Stone and other Kennedy supporters claim he was softening on Cuba and militarization, JFK did not shift course, but continued the U.S. obsession with Cuba and communism in Latin America. In November 1962, U.S. officials continued to insist that “the problem of Cuba and security transcends nuclear arms and purely military operations. Every Communist is dangerous. Cuba directly affects all the small nearby countries. These countries must develop socially and economically to offset Marxist propaganda. Communism will be no menace if countries are ruled democratically, and if assistance under the Alliance for Progress is forthcoming.”[52]

The continued U.S. assault on Latin America also belie the claims of Talbot and others that the president had alienated the CIA and was trying to weaken it, thus causing agents, especially those loyal to Dulles, to want him dead. Both before and after Dulles’s time as DCI, JFK used the CIA and other American groups (including prominently the AFL-CIO) to undermine and even overthrow Latin governments. Whether it be the JCS, NSC, FBI, or CIA, Kennedy was always involved in subversion, aggression, and intervention — at home and abroad.

In March 1963, Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Edwin Martin wrote a pamphlet on Communist subversion in the area which again showed that democracy and the Alliance for Progress were fig leaves for continued imperium. The U.S. had two goals in the region, to “isolate Cuba from the hemisphere and discredit the image of the Cuban revolution” and to “improve the internal security capabilities” of America’s allies there. Toward that end the U.S. had been training Latin American military personnel in riot control, counterinsurgency, intelligence and counterintelligence, psychological warfare, counterguerrilla warfare, and in other areas to maintain “public order” at U.S. military schools in the Canal Zone and Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Castro was the “aggressive element” that the U.S. had to confront, and JFK was even considering creating a Caribbean forced to use against guerrilla or insurgent groups.[53]

There was no hard evidence that JFK was having a change of mind or heart regarding the traditional U.S. role in Latin America. In May National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy presented the president with a report on Soviet “penetration” in the western hemisphere, and described the so-called Kennedy Doctrine. It was old Monroe Doctrine/Cold War wine in new casks. The declaration against the Soviet Union accepted the established premise that the extension of communist influence in the hemisphere was hostile to American interests and “such intrusion cannot be accepted,” and the U.S. and Organization of American States [OAS] would take the measures needed to prevent it “in the interest of freedom.” It also assumed that “the United States would take unilateral military action if necessary to prevent a Communist takeover of a Latin American government,” even thought that would raise “grave problems” between Washington and Latin America.

The group working on this study understood how delicate the issue of U.S. intervention on the internal affairs of another country was, so it had to be made effective with minimal opposition within the hemisphere. The declaration could be “surrounded with a good deal of hemispheric mood music,” but it would be a “major unilateral U.S. move” and would be met with “a lot of Latin American twittering” — especially in Brazil and Mexico. A potential way around that would be to have the declaration “issued in the context of some crisis in which in fact our decision to act would be generally approved. The hypothetical British Guiana case in the scenario is an example.”[54]

While Stone and others may claim JFK was prepared to thaw relations with Havana and open dialogues with other such groups to deescalate or even end the cold war, the record shows nothing of the sort. Kennedy ended 1962 in Miami paying public tribute to the Cuban Invasion Brigade and pledging that Cuba would be made “free” with Alliance for Progress and American help. In fact, the U.S. campaign of subversion and sabotage had continued even amid the Missile Crisis and afterwards. Kennedy did for a time try to tamp down the raids being conducted by Cubans out of Miami because they threatened to reignite a global political crisis with the Castro government and the Soviet Union, but never gave up on his goal of ousting Castro, even well into 1963. In an April meeting, JFK made clear he had not given up on removing Castro but insisted it had to be a Miami-Cuban effort and wondered “whether active sabotage was good unless it was of a type that could only come from within Cuba.”

At the same time Bromley Smith, the executive secretary of the NSC, presented an analysis that made it clear that Kennedy had decided to end the “restraint” he had shown on Cuba and was recommitting American assets to the campaign against Castro. “This paper,” Smith began, “presents a covert Harassment/sabotage program targeted against Cuba; included are those sabotage plans which have previously been approved as well as new proposals.” The NSC acknowledged that “while this program will cause a certain amount of economic damage, it will in no sense critically injure the economy or cause the overthrow of Castro.” It could however “create a situation which will delay the consolidation and stabilization of Castro’s revolution” and that was worth the U.S. effort.[55]

In fact, in Kennedy’s last public words about Latin America, in Miami on November 18th, he paid lip service to development or modernization — “There can be no progress and stability if people do not have hope for a better life tomorrow,” he said — but stressed the need to be on guard against communism in the region and be prepared to assist any state fighting off the Left. His rhetoric and plans for Latin America were not different than they had been in April 1961 when the U.S. invaded the Bay of Pigs. Communists were subverting and destroying development and if the U.S.-Latin alliance, manifested in the OAS, was to survive, it had to be prepared to aid any government requesting aid against forces deemed similar to Castro, and Kennedy emphasized that “my own country is prepared to do this.” He urged states throughout the hemisphere to “use every resource at our command to prevent the establishment of another Cuba in this hemisphere. . . .”[56]

So Kennedy, at the end of his life, was still a committed cold warrior in Latin America, not just in rhetoric but in practice as well. There are two key examples which demonstrate JFK’s continued hardline polices in the region, Brazil and Guiana. In Brazil, Kennedy laid the groundwork to oust the presidency of João Goulart, who was deposed finally in March 1964. Goulart was not himself a communist (in fact, there were just 25–40,000 communist party members in all of Brazil, a country of 75 million) but was allied with labor unions and other civil groups that had Left members and was pursuing a reformist agenda. In March 1963, Ambassador Lincoln Gordon began notifying Goulart that he would have to remove “anti-American” politicians from his inner circle or risk economic pressure from Washington. From then on, the CIA and Department of State were in frequent contact with anti-Goulart elements in the military, and also were creating paramilitary groups, to oust Goulart. Meanwhile officials from the AFL-CIO were making contact with labor representatives in Brazil to neutralize a group that once been allied with the government. Again, there is no evidence the Missile Crisis had forced JFK to reevaluate his hawkish policies or that he was trying to de-escalate the Cold War.[57]

Guiana, the hypothetical country in the May report, was also targeted by Kennedy. Kennedy showed no dovish epiphany as Stone and others would suggest when confronting the government of Cheddi Jagan, who “imperiled Latin America and the Alliance for Progress and threated the security of the United States,” as the administration saw it. Guiana, as part of the decolonization movement after World War II, was on the path toward independence, but Kennedy wanted Britain to “drag out” the process, while he also sent U.S. agents to the colony to undermine Jagan’s campaign and stir up racial tensions. Ultimately, Kennedy rejected Jagan (who was responsive to participating in the Alliance for Progress) and embraced a coup that later brought an authoritarian government to power in 1964.[58]

Such action, it should be noted, took place in areas beyond the Western Hemisphere too. In Iraq, Kennedy continued Eisenhower-era policies of opposing the government of of General ‘Abd-ul-Karim Qasim, a nationalist who’d overthrown the monarchy in 1958 and challenged the Anglo-American Iraq Petroleum Company’s (IPC) power. Because of U.S. opposition, Qasim sought more aid from the Soviet Union while also trying to reunite Iraq and Kuwait to reclaim the IPC’s oil concession. Kennedy increased the pressure on Iraq and the CIA worked closely with the Ba’ath Party and other groups in Iraq to oust and execute him in February 1963, after which the U.S. provided the new regime in Baghdad with military equipment, including weapons to use against Kurdish rebels, agricultural surpluses, and Export-Import Bank loans, while also encouraging private corporate investment in Iraq.

Even the New York Times, decades later, detailed the U.S. role in 1963, in an op-ed by ex-national security official and establishment scholar Roger Morris, who wrote that “Using lists of suspected Communists and other leftists provided by the C.I.A., the Baathists systematically murdered untold numbers of Iraq’s educated elite — killings in which Saddam Hussein himself is said to have participated. No one knows the exact toll, but accounts agree that the victims included hundreds of doctors, teachers, technicians, lawyers and other professionals as well as military and political figures.”[59]

Far from changing the U.S. approach to Latin America and other underdeveloped areas that had been doctrine since the days of James Monroe, Kennedy, as even moderate scholars who reviewed the record and the secondary literature about JFK in Latin America recognized, “in spite of his rhetorical promises, . . . was just another in a long line of cold warriors. Hence his efforts on behalf of the Third World were designed to combat communism, and only incidentally to improve the lives of people.”[60]

Revising Kennedy’s Legacy Post-Tet

Another piece to the story of Kennedy’s supposed desire to get out of Vietnam and reverse the Cold War that Stone did not engage is the fact that most of JFK’s associates who claimed that the president had soured on Vietnam and was going to withdraw did so much later, after he was assassinated and, importantly, after the war had taken a turn for the worse, especially after the Tet Offensive.

Kennedy’s friend and court historian Arthur Schlesinger’s “evolution” on JFK and Vietnam is quite telling. While the president was alive, Schlesinger agreed with him about the need to defeat the Revolution in the RVN and was optimistic about American prospects there. In his prize-winning A Thousand Days, published in 1965 with reprint in 1967, Schlesinger never made any mention of any plans to withdraw from the war (he did write that McNamara mentioned withdrawal as a possibility amid the Diem coup planning). Schlesinger then began to slowly turn when writing about Vietnam but even then questioning the war from the right, not in any dovish way. When his friend and hawk Joseph Alsop predicted victory in 1966, Schlesinger responded that “we all pray that Mr. Alsop will be right,” though he had his doubts by then. But he also wrote that withdrawal “would have ominous reverberations throughout Asia.” Presented with a chance to suggest JFK was going to get out of the war, Schlesinger did not say a word.

Theodore Sorenson, another Kennedy insider, made no mention of withdrawal in his 1965 book about the president but in fact said that JFK’s “essential contribution” was that he “opposed withdrawal or bargain[ing] away Vietnam’s security at the conference table.” JFK, he concluded, was going to “weather out’ the war. The president’s closest confidante, his brother and Attorney General Robert Kennedy, said in 1962 that the solution in Vietnam “lies in our winning it. This is what the president intends to do . . . . We will remain here until we do.” Like virtually everyone in the administration, Bobby Kennedy’s concern about the ability to win with Diem in charge was that he was damaging America’s efforts in Vietnam and stressed that the U.S. needed “somebody that can win the war,” and after 22 November 1963, he continued to support Lyndon Johnson’s continuation of his brother’s policies there until a break a few years later.